While I know that Potong Pasir literally means 'cut sand' because of the many sand quarries in the area pre-war and for a few years after, I didn't know anything else about the area. I can't quite call it town because Singapore is so small that each 'estate' is literally an 'area'. Not quite a town even. Anyway.

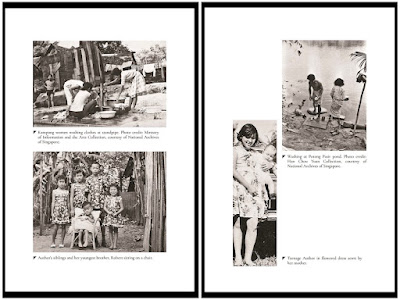

I had to know more about Potong Pasir back then. So I picked up two books by Josephine Chia. While the author isn't new to me, these two books are — 'Kampong Spirit' (2013) and 'Goodbye My Kampong' (2017). These books hold the author's childhood memories of growing up in a kampong in Potong Pasir.

The language is a tad, reflective of the way authors of a generation write. It's highly repetitive and sometimes a tad over-detailed and slow. The author writes like the way an English school teacher talks. She has enormous respect for her mother, and her stories about her mother, especially the sewing of new curtains and clothes are repeated almost word for word thrice over. These repetitive narration of the personal details, is a bit overdone.

But I get how she is grateful to her mother for pushing the case to allow her to go to school, to learn to speak English, to write, and have the opportunities to expand her horizons. Those are the precious opportunities not available to many kampong dwellers without money.

Kampong living was truly a different way of life. I can't call it better or worse. It's simply different. People lived life at a slower pace. Time and steady urbanization have forced all kampongs to disappear (except one — Kampong Lorong Buangkok built in 1956, and is still home to 25 families on half the size of the land then, on three football fields), and in its place, the buildings we know today, and many more being built.

It's ironic, isn't it, that when we travel now, we seek out nature and 'kampong living'.

'Kampong Spirit - Gotong Royong' (2013) / Life in Potong Pasir 1955-1965

This book addresses the author's growing years before Singapore split from Malaya became independent in 1965. Nobody spoke Mandarin. Everyone spoke Malay and dialects, and some spoke English in order to be employed by British firms.

The author's Peranakan family lived in a Malay kampong in Potong Pasir, as opposed to a Chinese kampong that reared pigs. In post-war those years, Kampong Potong Pasir lacked electricity and running water. Toilets were communal, and people used chamber pots at home; no flush toilets, no toilet paper. There wasn't such a thing as a refrigerator for them either. Electricity only arrived in the village via a generator in 1962. The family were poor too, and food wasn't plentiful. But there was harmony, help and camaraderie in the kampong. Life was hard but seemed happy.

Born in 1951, the author lived through the Hock Lee bus riots in 1955, David Marshall becoming the first Chief Minister of Singapore, the political excitement of all the political parties and PAP's rise to power in Lee Kuan Yew becoming the first Prime Minister of Singapore in 1959, the big fire at Kampong Bukit Ho Swee, the chaos of Konfrontasi (the MacDonald House bombing happened today in 1965, 10 March), racial riots and bombings, and the ultimate painful separation of Singapore from Malaysia, et cetera.

She tried to link those historical events to the happenings in the kampong, and in her family life. She mourned the loss of her best friend, an older girl named Parvathi who at 17 years old, chose to take her own life rather than marry a husband she didn’t want but her father insisted on. In those days, uneducated girls are totally at the mercy of their families.

This book ended in 1965, with the separation of Singapore from Malaysia. The author was 14 years old, and getting an education and beginning to dream of more schooling and becoming a writer.Sports back then were a huge thing. It seemed to have united the kampong and residents, regardless of race and religion. Sports united a fledging country when our athletes won many medals in the SEAP Games in December 1965. Is it still a thing now? Sports in Singapore is like... muted — a good to have, and a wonderful activity for school-going children and young adults, and that be all.

Well, thanks for kicking us out, Malaysia. Giggled when a familiar term came up, 'OCBC' — orang cina bukan cina. LOL Isn't this identity crisis still prevalent today, albeit in a different manner?

In many ways, when we didn't have television, the horror of an incident was not brought home to us so tangibly. But now the sight of moving images with all their sound and fury made it hard to escape the drama and pain of the people engaged in conflict. Technology was both a gift and a curse.

'Goodbye My Kampong' (2017) / Potong Pasir 1966-1975

This is like a follow-up to Josephine Chia's first book about Kampong Potong Pasir which ended in 1965 when she was 14 years old. So this one addressed the next stage in the years 1966-1975, when people have already chosen their identity as Singaporeans in a brand new Singapore. When the changes came, they arrived fast and furious.

"Though this book is specifically my final goodbye to my own kampong, it is also a goodbye to all the kampongs in Singapore and a now-extinct way of life."1966 saw the protests by the Chinese-educated students of the Nanyang University, who demanded jobs in the civil service, and were upset that only English-educated students got that privilege. Mandatory National Service call-ups began for young men. The author's father also died from abdominal cancer. It was quick. Floods were still prevalent in kampongs and villagers still die of cholera after.

I grinned when it mentioned Led Zeppelin's canceled show in Singapore in 1973 over their long hair, and how the Bee Gees refused to play a second show after having to wear hairnets on their first night of the tour here. Also, 'STOP AT TWO. Boy or Girl, Two is Enough.' Ahhh yes. This was the period of stupid social campaigns.

And I had clean forgotten how the Malaysian government wanted to extort $70 million dollars from us if we wanted to keep the acronym of MSA (Mercury Singapore Airlines) for our national carrier. Walao, they don't even want us to use MSA because it's too close to MAS. FINE. SIA it is. And SIA soared. Remember this is what in essence the Malaysian government is. Tsk tsk.

The author graduated as a full-fledged dental nurse. Her other best friend Fatima would marry and move to Kuala Lumpur.

The book ended in 1975, as families in the attap houses in Kampong Potong Pasir packed up and prepared to move out. Their landlord was relocating soon and wanted his compensation from the government. Many moved to better housing and amenities. But nobody was prepared for the loneliness and silence in a complete change of lifestyle. In 1975, the author was then 24 years old, and had applied to university to read literature, and had been accepted. She dared to dream of a future and better prospects.

The end of the kampong came swiftly. Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew was tough and decisive. No more firecrackers, no more kampongs, no more cholera. Building a solid military and a strong economy, modernization and hygiene were key words. Kampong Potong Pasir along the Kallang River was prone to floods, and the last major flood in 1978 devastated the remainder of the village.

Two thousand poultry and pigs died, floating belly-up down Kallang River and making a great stench. The low-lying farms and houses were destroyed by the heavy rain and mudslides. After that, the final clear-out began. Bulldozers, diggers and mechanical cranes invaded the village, like alien monsters. They uprooted ancient trees unceremoniously, some of which we had climbed and loved. The attap houses were broken and crushed, years of history tumbling down and disintegrating. None of these things mattered to the labourers. They did not feel what we felt about the place. On the outside, it was just a shanty village of wooden houses with old-fashioned attap-thatched roofs. How could they know what the village had meant to us?

The whole kampong was razed to the ground. Totally wiped out.

The elderly folks of that era who moved from kampong to these high-rise flats struggled to cope. Living in flats is a different thing man. We certainly don't talk to our neighbors so much. It was a changing landscape, a changing city, and it's very discombobulating.

Time and urbanization wait and care for no man. It is what it is. Preservation and heritage took a back seat to city-building and country-saving. We had an economy to churn, jobs to create, and people to feed. Those were more important than any arts and culture campaigns to remember any sort of 'heritage'. 60 years on, in 2025, these years would become our heritage.

Selamat tinggal. Those were the days.

No comments:

Post a Comment